“All this happened, more or less.”

Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five.

The popular notion that creative people don’t make good businesspeople has occupied my mind for a while. It gets validated by actual stories and urban legends of artistic folks who struggle to get commensurate financial rewards or fame for their talents. The reason tends to be reduced to some irresponsibility and laissez-faire behaviour common with creative people. Parents and teachers know that one child who possesses sparks of brilliance but exhibits traits that impede the ability to flourish.

I’ve read quite abundantly about the lives of creative people in history who have wrestled with the confluence of forces that come between them and their talents. Sometimes, these are disguised blessings. The forces may charge them towards creating beauty or become the means to make sense of circumstances. One only needs to read about the poverty that Charles Dickens experienced before generations could enjoy the beauty of his Victorian novels. Or Frank McCourt, of Angela’s Ashes fame, to wonder how he was able to tell such childhood horror story with humour and grace.

Most curious to me was the capitalist dynamics between creators and the economic realities of their time. The fate of the artist, it seems, is tied to the prevailing economics of the day. For instance, the history of the Renaissance is replete with artists being commissioned by wealthy patrons to whom artists must impress by creating the finest work to guarantee retainership or to maintain their celebrity and income in the face of rivalries – cue in the famous rivalry between Brunelleschi and Lorenzo Ghiberti. As the European era of artistic and intellectual flourish, the Renaissance bore every quality that modern business textbooks would illustrate as innovative, competitive, and with rewards distributed according to the Pareto principle.

As the era showed, it was not merely enough to be talented. It was necessary to find the balance between attracting the attention of patrons and managing the dynamics of sustaining commissions. One might say, in modern speak, that to survive, an artist needed a healthy blend of talent, competitive edge, business savviness, and luck. These informed how Renaissance artists and thinkers produced the magical, the sublime and the transcendental.

The artist’s sustenance and survival take different forms, which include the susceptibility to exploitation.

The infamous relationship between Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison comes to mind. (Having a surname that inspires a future electric car company doesn’t count as a reward). Moreover, in the extreme is the tortured artist or gifted mind whose eccentricity acts as the factor fuelling genius and the demon tormenting it. The poster child here is the mathematician John Nash whose story, narrated in The Beautiful Mind, disturbed me in no little way when I read the book before watching its film adaption.

As these thoughts occupied my mind, I was already working as a copywriter in an advertising agency. In the advertising industry,

there are people called creatives. They’re simply people jostling in creative departments to find tricks to convince consumers to buy products. The stereotype about these characters – being in a class of eccentrics, scatterbrains, rebels, etc. – is that they sit in front of a computer or a corner of the office, perhaps wear more than enough piercings on their faces or tattoos or distressed jeans or any kind of accessories that signal quirkiness. These characters, when attempting to solve a client’s problem, reach into a reservoir of ideas acquired from years of slugging it out in the department or evoking metaphors or from furtive checks of previously done campaigns. The purpose is to unearth new magic that will satisfy a client’s request. For the most part, it’s a fun job, but….

But the creative, unlike his (or her) counterpart in other departments, is usually not involved in the serious duty of growing the business through finance, business development, management of clients and suppliers, etc. Creatives may take the shine for conceptual outputs, but the structural lifeblood of the industry depends on non-creative endeavours. I didn’t think there was something wrong in the arrangement, or if there weren’t means of finding balance, but I noticed the reinforcement of the trope about creators – that they’re not the businesspeople. (Here, I must say that I know successful creatives who are businesspeople, but the numbers are in the minority).

I observe this phenomenon among my gifted friends - writers, poets, painters, singers, stage actors, etc. (I must admit, this wasn’t a neat experiment. I merely gleaned from what I was privy to in their lives). I could tell how some of them struggle to reconcile the wellsprings of their inner worlds – where they conceptualise freely – with an outside world that demands structure and discipline. In psychological terms, it would be the struggle to combine open-mindedness with conscientiousness. It’s rare to be equal part blessed with this at a high level because the animating spirit of the creator is to roam freely without strictures whereas the animating spirit of executing ideas requires strictures.

On the other hand, as I was an advertising creative director with flair for literary, cultural, and entrepreneurial pursuits, I had a fair share of creative people in the mainstream who reached out to me to get sponsorships from some of my clients. This ranged from a photography exhibition to film making, display advertising or music festivals. To their surprise, I usually review their proposals in ways that fit their ideas into a client’s business objective. A few of them would naïvely frown against it as though I was hurting their babies. It turned out that those able to get sponsorships or at least got to the front door were those who were reasonably adaptable. Again, the purist creatives left me wondering about the lives and future of the stubborn types in the world of business.

I started a business sometime in 2012 partly to expose myself to the realities of running one, as a creative. It allowed me to test my hypothesis and to see the extent to which I could manage it. To be honest, it wasn’t the easiest task as I contended with rather mundane tasks. Attempts to hack this through various means didn’t quite work. By this time, I had read research findings of the existential crisis of creative people and the wirings of their brains, some of which may manifest in restlessness, forgetfulness, aloneness, extraversion, and even ADHD.

So I thought perhaps I should consider immersing myself in business academically. After all, I’ve had a first taste of running one and the gaps are well known to me. These morphed into questions of why most creative people struggle with turning their ideas into ventures or, if they have, why they struggle to scale them. And more so, how to maintain creative excellence in the face of forces demanding compromise. Besides, there was a new world order where creatives were experiencing disruptions from new technologies and business models, where the terms of engagement are at the mercy of algorithms designed by companies that seem to control nearly every aspect of the value change.

I reckon that a formal understanding of business may offer answers, and so, as a senior exec, I began window-shopping for an MBA programme. I wanted one designed for the creative industry. I already knew the MBA programme of the Berlin School of Creative Leadership. I came close to experiencing the school in 2010 on a visit to France at the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity, an industry event that celebrates creativity in marketing communications. The school hosted a workshop. While I didn’t attend, its presence at the event heightened my interest. Some years later, I applied for admission. I wrote the required essays to be able to get some scholarship discount. I got the scholarship, but I couldn’t rely on my inconsistent salary (at the time) to fund the programme.

I continued to search top schools in different countries. MBAs with a focus on the creative industries are rare. And I wasn’t sure about the reputation of the few I found. Reluctantly, I applied to some although they mostly distinguish themselves through concentrations like Finance, Project Management etc. Everything but the creative industry! I would study their syllabi and be overwhelmed by the details of their finance modules. Dear Reader, as contradictory as it may seem for someone in love with entrepreneurship, academically speaking, finance isn’t my favourite sport. For me, let’s discuss numbers and money at the practical level. Don’t involve me in the classroom version. My brain, no matter how much I try, freezes. This single reason made me shelve the prospect of a general MBA.

So I thought, what if there was a master’s programme that seemed like a decent MBA alternative and whose content aligns with my expectations – with elements of creativity, businesses, and technology? A sizeable period of the pandemic lockdown went into searching for schools, studying curricula, reaching out to people, emailing schools, reading reviews, etc. This LINK was valuable. But when I settled for the UK, I relied on the Guardian UK university ranking where the university I picked, the University of Strathclyde, with its robust master’s programme in Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Technology (sweet name 😎), ranked high among 121 universities.

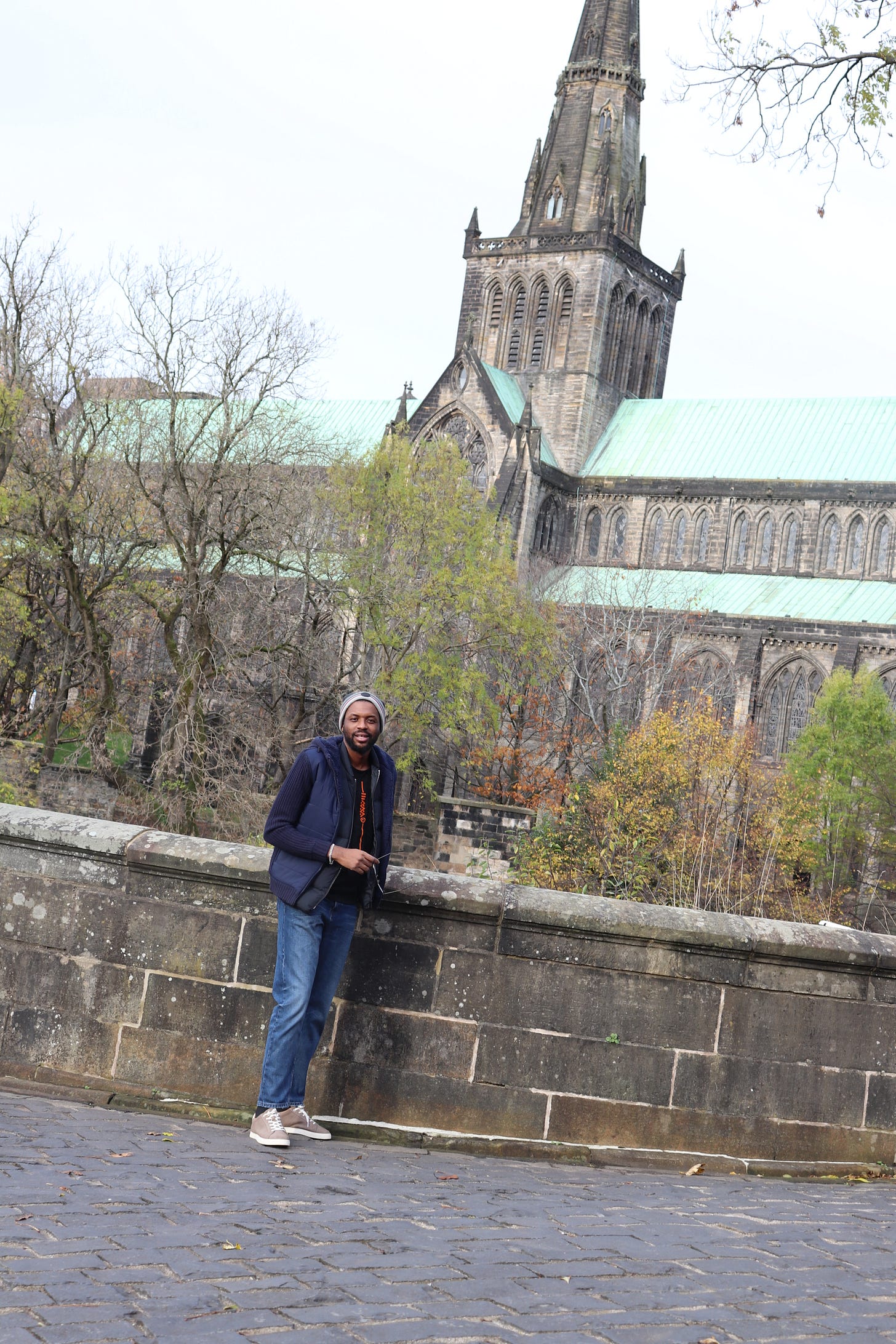

This is already a long essay. It's my 10th month in quaint and friendly Glasgow, surviving the rather intriguing weather, making new connections in a community that looks like the United Nations, travelling to neighbouring towns, walking into statues and monuments of famous British names that feature in my primary school textbooks, performing some poems in the town Robert Burns lived, being utterly bewildered by the amount of alcohol this city guzzles, being the oldest guy in a class of mostly cool people, getting carried away by new fascinations in class materials and forgetting they’re for assessments, and surviving class works (read as surviving the data and finance modules🙄). And most fun, I’m fascinated by a life stripped of my old self and comfort and experiencing a different type of bliss. (As a Nigerian reader may understand - no one has called me “Oga Chris” in about 10 months, lol).

So far, as my Mindset module shows, the notion that (creative) people don’t make good businesspeople might be a misdiagnosis of the situation, as there are cognitive hacks to help folks grow entrepreneurial mindset and grow sustainable ventures.

Time would tell if studying at Strathclyde has been a good investment. But first, I have a Scottish train to catch for sightseeing and whatnots.

Please use the button to leave comments and remember to share :)

It is true that some creatives or(artists) have managed to combine their art with on-hands entrepreneurship, an Udeme and Adisa readily comes to mind.

However most have not been able to.

Some may even view it as some kinda taboo. Although, I have no evidence to back my next postulation, I think a lot of the unreceptiveness, or should I say a lack of the dare factor of creatives may not be unconnected to how their brains are wired.

To some, the contentment found in their art and whatever applause that comes with it, is more than enough satiation for their souls. And to some others, it is clearly a phobia, they are willing to live with for the rest of their lives.

As always, fabulous writing, Oga Chris (I broke the 10month jinx. lol)

This totally resonated! hilarious and educative. The look to avoid £20 though :)