Banksy’s notoriety has been one of fascination rather than crime. As someone with a mostly sceptical view of modern art, I include Banksy in a rare group of artists pushing art without the pretensions that tend to describe modernist expressions. The word “kitsch” takes its place here now, as it has come to epitomise the character of modern art in my observation.

My willingness to extend grace toward any new creation usually fails when new installations or exhibitions pop up somewhere prompting one to wonder about their value or what they purport to embody - be it conceptual, emotional, transcendental, personal, or provocative. There’s often a stark contrast with works of previous eras when art was easily objective from the strands of context in which works emanated.

But these days, the argument of art as subjective seems to be a ploy to mask works without any sort of redeeming value other than the intention to give relevance to their creators in a world where shock, pop, dangerous ideologies and technology algorithms modulate creative expressions. This appears to affect every aspect of creative expression - architecture, literature, film, etc. It’s as though humanity has agreed to bargain finesse for convenience, rigour for ease, and profundity for spectacle.

Not Banksy. Provocative, yes. Subversive, yes. There’s an inherent value in his creations that forces the mind to pay attention to contexts within the mystery in which the works are shrouded. He challenges conventions while still retaining a coherence that does not offend reason and common sense. He entertains without being garish. Despite the pop resonance of his work, they are devoid of sentimentality.

I’ve followed Banksy for as long as I can remember - or for as long as his new work hits the news and the media scurry to uncover the mystery - and the face - behind the work. When I saw the announcement about Banksy’s exhibition, cheekily christened - CUT & RUN, I knew I was not going to miss it for anything. But I didn’t realise how quickly the ticket would sell out, so I was left with refreshing the ticket website for a lucky announcement. It took days of multiple attempts before new tickets and days were opened. Perhaps, the scarcity was a marketing trick to project Banksy’s invisibility into ticket availability. If so, it’s brilliant.

I eventually got a ticket.

The D-day. Two vertical banners drape down from the Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA), announcing the exhibitor and the exhibition. Noticeably, a cone replaces the A in Banksy’s name, a nod to the traffic cone that the people of Glasgow place on the statue of The Duke of Wellington, itself an iconic feature of the city.

I have visited the gallery a couple of times. But I have never had to pay or queue to watch an exhibition. After rushing my food at a nearby Thai restaurant, I joined a queue as we filed in amidst an atypical security set-up. The security shared pouches where phones were to be kept to deter recordings. As typical, the Glaswegian weather, the one I described in a poem as possessing a “mercurial gut - belches, spits, pisses, pukes, farts, in motleys of moods and wet tantrums,” began to prove itself. We filed in before any downpour or wild wind.

I was looking forward to seeing “Love is in the Air” (2003, West Bank), possibly my favourite of Banky’s stencils. The mural first appeared on a wall somewhere around the divide between Israel and Palestine. The flower thrower’s pose suggests a violent swing of what should have been a stone or a Molotov cocktail. But it is replaced by a bouquet, and the pose transforms into a desperate gesture to express love and peace. Its display in one of the most hostile regions in the world makes it more telling. It was lovely seeing it.

Visitors walk snakily through the works. I realised that I’m familiar with most of the works but seeing them at close range, with their descriptions, gave me a different experience. More so, Banksy’s mystery writ large everywhere as a backdrop. The interior design seemed like a movie production set - props and crew attend carefully to an idea.

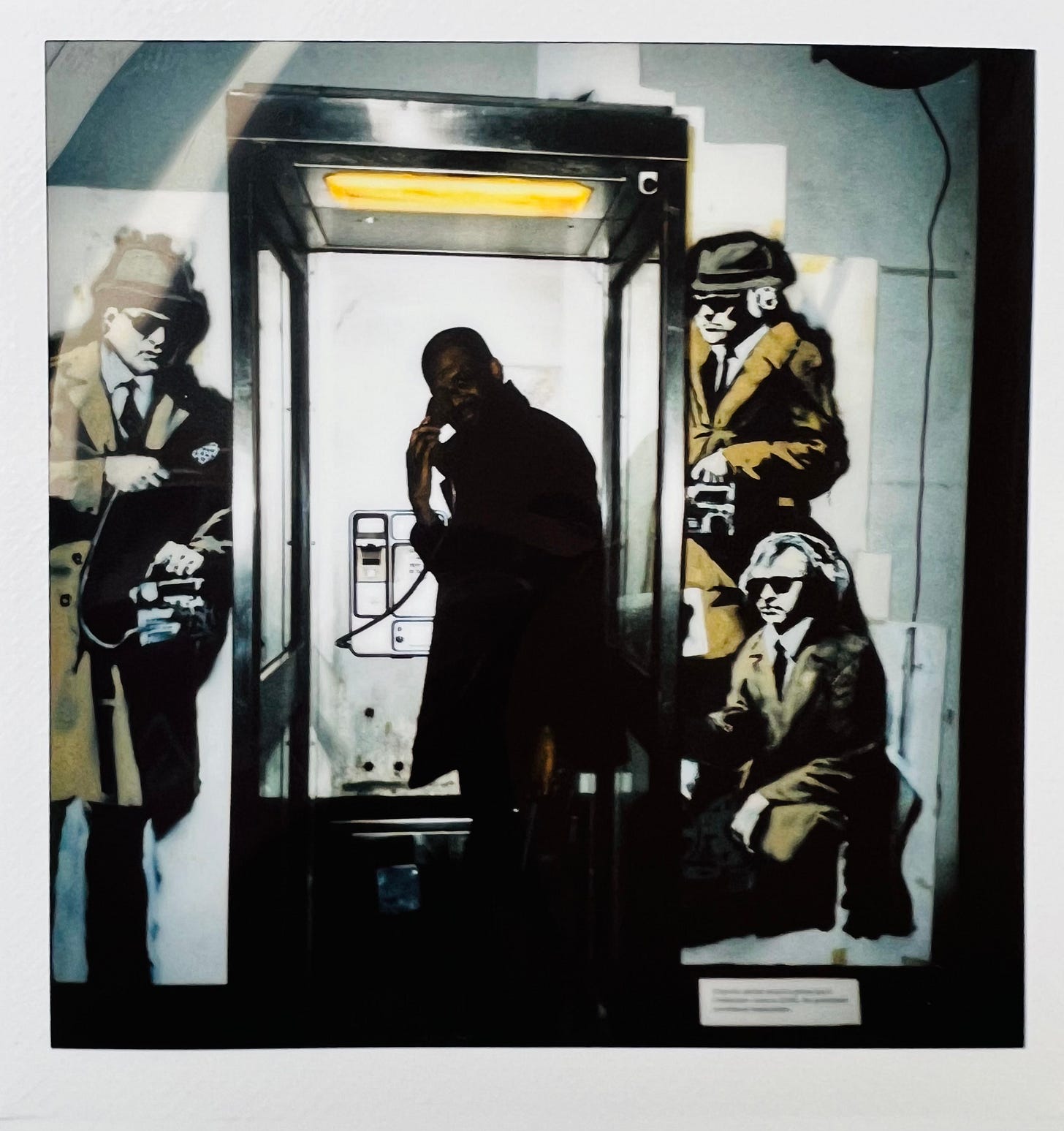

An usher invites people to engage with one of the works, “Spy Booth” (2014, Cheltenham, England). It was Banksy's response to the government's controversial surveillance project. Visitors were given a Polaroid image after. Talk of surveillance for a souvenir.

It was a great exhibition. (The BBC footage of the exhibition).

In retrospect, I wonder if Banksy himself was present, concealed or camouflaged among the throng of visitors or crew. If only I could detect him, I would have thrown a bouquet of respect at him.